“…We dedicated quality time to explore Vancouver, its intriguing urban environments. The city is impressive, modern, diverse, busy, with plenty spots to stop by and simply look at. We carried with us a ‘step counter,’ a wrist-watch-like device that told us the number of steps walked daily: a grand total of 234,190 steps during two weeks, about 117 km or 73 miles…”

By Guillermo Paz-y-Miño-C

I finally had the time to upload some images from our visit to Vancouver at the end of July and beginning of August, 2018. My collaborator, Avelina Espinosa, and I attended the 5th joint meeting of the Phycological Society of America and the International Society of Protistologists (the latter, ISoP, the society to which we belong). The meeting took place at The University of British Columbia. Here are the PDFs of the full program and abstracts of the presentations (200 talks, 100 posters).

In the past, I have posted photographic/academic reports of similar ISoP meetings in Prague (2017), Moscow (2016) and Seville (2015). Previous conferences have taken place in Banff (2014), Oslo (2012), Berlin (2011), and Kent-Canterbury (2010), which we have attended as well (no postings of those years, but see photography and science traveling during the past 15 years).

The ISoP meetings are medium in size (in the hundreds of attendees) and broad in scope. They gather scientists from all over the world, specialists on: systematics of unicellular eukaryotes (= protists), diversity and biogeography of these organisms, functional ecology (particularly aquatic environments), impacts of climate change on microbial communities, the origins of cell organelles and their physiology and metabolic pathways (e.g. chloroplasts, mitochondria), among other topics. Some are evolutionary biologists working on the genetics, behavior or health aspects of protists. A few study the origins and evolution of multicellularity, for which microbes are good models.

We presented a poster (below) at the meeting (Kin Recognition in Protists and other Microbes: A Synthesis), which summarized the content of both our latest book on protists and a review article just published in the Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. Here is the poster’s abstract: “KRP-and-OM is the first scientific compilation dedicated entirely to the genetics, evolution and behavior of cells capable of discriminating/recognizing taxa (other species), clones (other cell lines) or kin (as per gradual genetic proximity). It covers the advent of microbial models in the field of kin recognition; the polymorphisms of green-beard genes in social amebas, yeast and soil bacteria; the potential that unicells have to learn phenotypic cues for recognition; the role of clonality and kinship in pathogenicity (dysentery, malaria, sleeping sickness and Chagas); the social/spatial structure of microbes and their biogeography; and the relevance of unicells’ cooperation, sociality and cheating for our understanding of the origins of multicellularity. With 200+ figures, KRP-and-OM (the book) is conceptualized for a broad audience, including researchers in academia, post doctoral fellows, graduate students and research undergraduates.”

Click on the image below to enlarge the e-version of the poster [click again to see it in real size]:

Before and after the conference, we dedicated quality time to explore Vancouver, its intriguing urban environments. The city is impressive, modern, diverse, busy, with plenty spots to stop by and simply look at. We carried with us a “step counter,” a wrist-watch-like device that told us the number of steps walked daily (grand total 234,190). From it we estimated the distance traveled by foot during the two weeks spent in situ (117 km or 73 miles). The photographic report follows below. If interested click on the images for higher resolution; click twice if you want to see them real size.

The urban experience

We walked 234,190 steps (about 117 km or 73 miles) during 14 days (8.5 km/day or 5.3 miles/day); drove only 652 km or 405 miles (not much in comparison to other trips); and took 1,808 photos (a bit short this time); 82 of the images (4.5%) were shared on social media (Facebook and Twitter). In summary, we had an “urban experience” (walk/drive) with some wilderness and nearby sightseeing. Marutama, in the Westend of Vancouver, was the best restaurant for Ra-Men (specially Tan-Men).

The images © below follow a chronological order of our trip, well, as much as possible. Enjoy.

Above: always needed, maps, more so in Vancouver, a large city with intricate traffic.

Above: Montreal; we flew from Boston to Montreal, transited for an hour and continued to Vancouver.

Above: “Closer to Mars,” figuratively, of course. On our way to Vancouver.

Above: at our hotel; we actually stayed, for the duration of the meeting, at the University of British Columbia’ residence for visitors (UBC Conferences and Accommodation, West Coast Suites). Quite impressive, well kept, comfortable and elegant, with a nice kitchen, better than the expensive hotel we later moved into (downtown) for the rest of the visit.

Above: Masmasa’lano, Multiversity Galleries, at the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia (UBC).

Above: Buddha, Multiversity Galleries, at the Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: A close up of Buddha, Multiversity Galleries, at the Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: Carved on wood at the Welcome Plaza, House Post, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

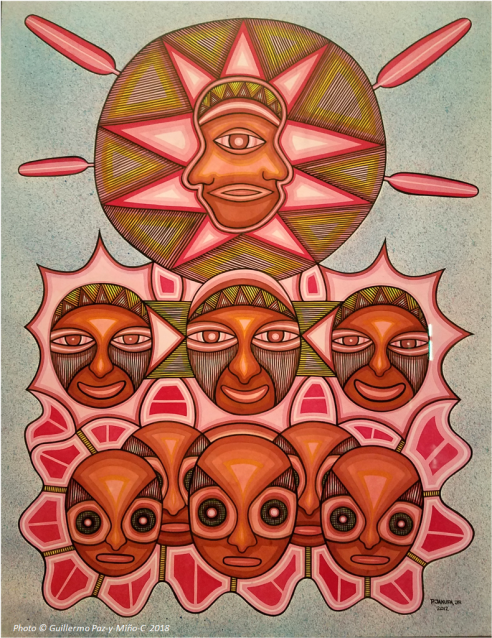

Above: Carnival Mask, Multiversity Galleries, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: Haida Bear by Bill Reid, Great Hall, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: Haida Bear by Bill Reid, Great Hall, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: More wood carving, House Post, Great Hall, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: Outdoors of the Museum of Anthropology, image taken from the grounds, UBC.

Above: Raven Discovering Humankind in a Clamshell, The Bill Reid Rotunda, Museum of Anthropology, UBC.

Above: Carving at the temporary exhibit Culture at the Centre, Museum of Anthropology, UBC

Above: Moon Gate Tunnel at the UBC Botanical Garden.

Above: Tree Walk at the UBC Botanical Garden.

Above: Wild flowers at the UBC Botanical Garden.

Above: Leaves and Mosses at the Nitobe Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Log Bridge at the Nitobe Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Memorial to Professor Nitobe at his Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Pacific Bell and Bell Tower at the Asian Studies outdoors, UBC campus.

Above: Trees and Shrubs spot at the Nitobe Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Water Lilies and Duckweeds at the Nitobe Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Water Lilies and Duckweeds (B&W) at the Nitobe Garden, UBC campus.

Above: Kids playing at the Spanish Banks Beach Park.

Above: The Friendship Bench at the UBC campus.

Above: It’s A Mystery by John Nutter at the UBC campus.

Above: Blue Whale at the Beaty Biodiversity Museum, UBC campus.

Above: Centre for Business Ethics at the UBC campus.

Above: “I Want It All I Want It Now” at the main library, UBC campus.

Above: Quantum Matter Institute at the UBC ccampus.

Above: Urgent Care Centre at the UBC campus (examine this photo carefully).

Above: Fees apply to all at the Urgent Care Centre, UBC campus.

Above: “The Nest” at the UBC campus.

Above: Victory Through Honour Pole by Ellen Neel, at the UBC campus.

Above: Danbo Restaurant in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Danbo Restaurant in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Blue Buildings and Blue Sky, downtown Vancouver.

Above: The Burrard St. Bridge in downtown Vancouver.

Above: The Burrard St. Bridge in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Is this scientifically true? Granville Public Market, Granville Island.

Above: At the Granville Public Market, Granville Island.

Above: “Three Berries” (well, sort of) at the Granville Public Market, Granville Island, Vancouver.

Above: At the Granville Public Market, Granville Island, Vancouver.

Above: Downtown Vancouver.

Above: Light-Shed, Vancouver Harbour.

Above: Vancouver Harbour.

Above: Sky Jump at the Whistler Olympic Park (located Northwest of Vancouver).

Above: Our rented truck at the Whistler Olympic Park.

Above: Pre-entrance to the Vancouver Public Library.

Above: Pre-entrance to the Vancouver Public Library.

Above: The iconic Steam Clock in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Marutama Ra-Men, the best in town; there are two locations in Vancouver.

Above: Ra-Men being made at Marutama in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Tan-Men Mild at Marutama Ra-Men.

Above: Plain rice at Marutama Ra-Men.

Above: Kakuni Pork Belly at Marutama Ra-Men.

Above: The Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden in downtown Vancouver.

Above: Trees Falling at the Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden, downtown Vancouver.

Above: The Details of a City, downtown Vancouver.

Above: The Lions Gate Bridge, downtown Vancouver.

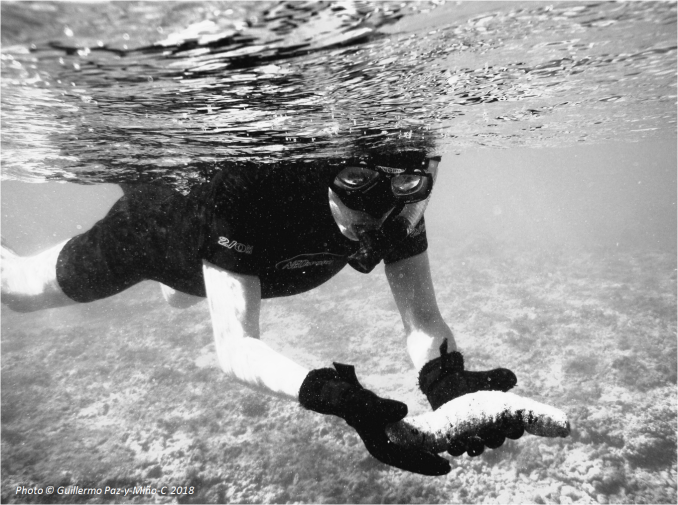

Above: At the Vancouver Aquarium.

Above: Chrysaora fuscescens at the Vancouver Aquarium.

Above: More of The Harbour.

Above: A-Maze-Ing Laughter by Yue Minjun, downtown Vancouver.

Above: Space Centre & Museum of Vancouver.

Above: And a close up of the Space Centre & Museum of Vancouver.

Above: Vancouver Art Gallery, in the downtown.

Above: “A Rushing Sea of Undergrowth” by Emily Carr 1935, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Above: “Ayumi” by Corey Bulpitt at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Above: Buckminster Fuller‘s Geodesic Dome at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Above: “Peter” by Corey Bulpitt at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Above: “Tarah” by Corey Bulpitt at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Above: The famous Morgan Guitars exhibited at the Vancouver Airport.

Above: “Meeting is Over”…

Above: Rain and Propeller, Vancouver Airport.

Above: Sunlight and Propeller, light bends, closer to Boston.

— EvoLiteracy © 2018.

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook @gpazymino and GPC-Facebook

You must be logged in to post a comment.